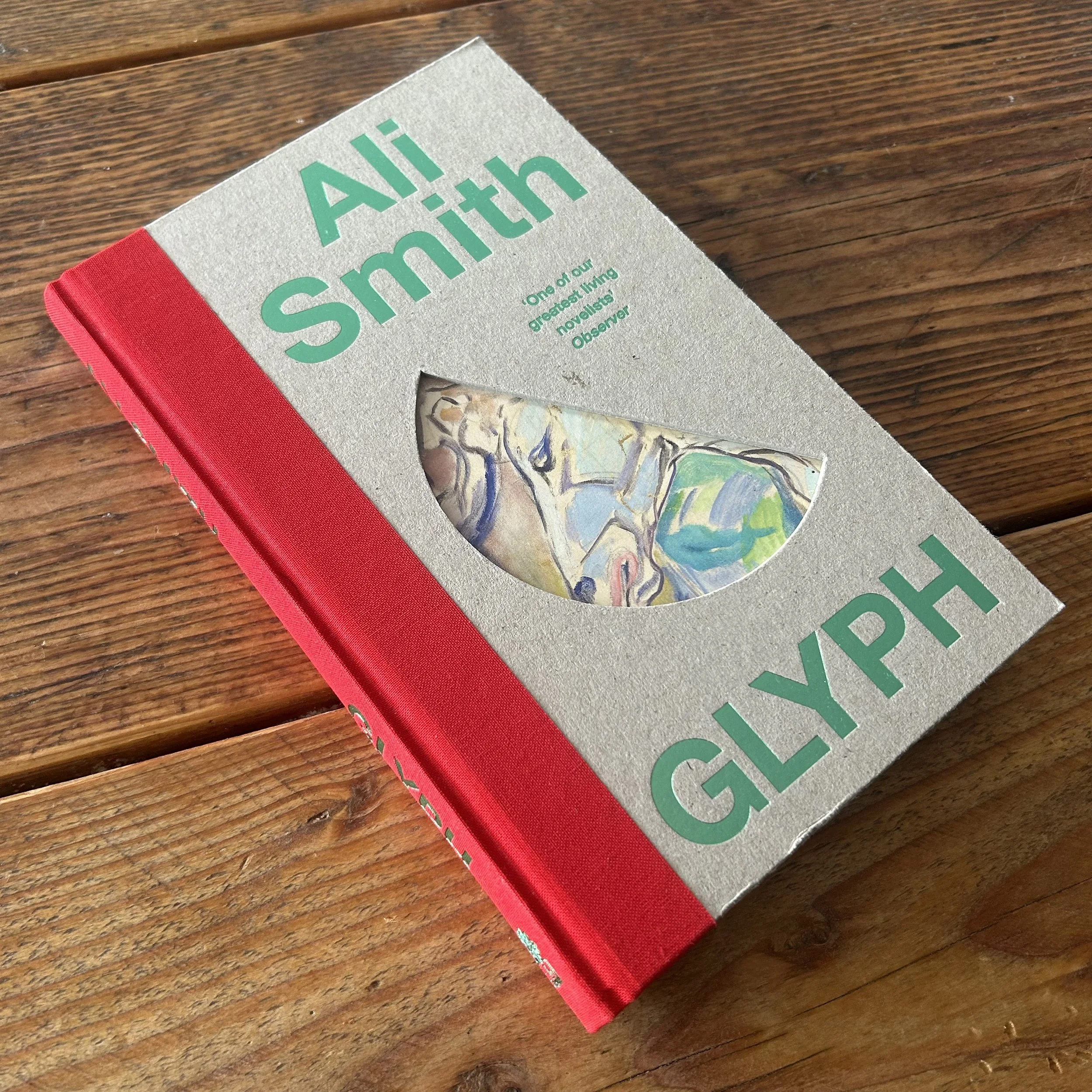

Glyph (2026)

Why this one?

After a bit of a false start (ages ago now) not getting on with Autumn, I read How to be both as part of my Women’s Prize winners project and then jumped back to The Accidental, and loved them both. I was similarly fond of last year’s Gliff, to which this is ‘family’ (but very much not a sequel), in Smith’s words.

Ali Smith (1962- ; active 1986- ), was born in Inverness, Scotland to working-class parents. She studied English Language & Literature at the University of Aberdeen and then began a PhD in American and Irish modernism at Cambridge. During this time she began writing plays and so did not complete her doctorate. In the late eighties she regularly had plays performed at the Edinburgh Fringe, before focusing more attention on prose, with her first book of shorts, Free Love and Other Stories, published in 1995.

Her first novel was 1997's Like, which she followed with Hotel World in 2001. The latter was shortlisted for both the 2001 Booker (losing out to Peter Carey's True History of the Kelly Gang) and the same year's Women's Prize (won by the rather lovely The Idea of Perfection.) She repeated the same feat with 2005's The Accidental (this time pipped by John Banville’s surprise winner The Sea and Zadie Smith's On Beauty respectively.) How to Be Both won the Goldsmiths Prize and Costa novel prize in 2014 before finally giving her the Women's Prize in 2015. She has since written four seasonal 'state of the nation' works beginning with 2016's Autumn (also Booker shortlisted) which was written in the immediate aftermath of the UK's 2016 Brexit referendum, plus a fifth in the series, Companion Piece.

Thoughts, etc.

Glyph focuses primarily on two sisters: Petra, the elder, and Patricia (or ‘Patch’). The novel is set in (roughly) the present day, but flashes back to look at the sisters’ childhood in the 1990s. At a family party, an elderly relative tells the story of seeing a man utterly flattened by tanks in France in the Second World War. The sisters create an imaginary friend from the unknown man, and name him ‘Glyph’. This story, and another war tale of a man in the First World War who was executed for desertion (following his unwillingness to put down a blind horse), continue to the haunt the sisters in the present day. Petra is still searching for details of the flattened man, and calls Patricia for help following years of estrangement after she believes she sees the ‘ghost’ of the blind horse in her bedroom, which (by whatever means) has been trashed.

It was always going to be interesting to see what Smith did with the ‘follow up of sorts’ to the near-future dystopia of Gliff. The outcome is typically unexpected - while in some senses a prequel (there are direct references to the pollutant that causes the ecological catastrophe that forms the backdrop for Gliff), it resists this simplistic definition by setting Glyph in a world in which its predecessor exists as a work of fiction. In some senses it seems to be saying that the first book was the ‘fantasy’, the elusive attempt to capture reality via means of imagining its future. This one (named with a word that’s more clear and fixed in its meaning and allusions - a permanent mark; something real and documented) is the grounded reality. As the characters in this book discuss Smith’s last work, taking words out of the mouths of some reviewers and describing it as too ‘on the nose’ and suchlike, we are faced with a book that is even more so. It may be a book with ghost horses and imaginary friends, but both are firmly rooted in true stories, and importantly stories of the horrors of war which are all too clearly connected to the horrors of our present day world.

Reality, since Gliff, has (probably in any sense to Smith’s surprise) advanced somewhat in the direction of the police/surveillance state that she envisaged in that first book. In this one, Patricia’s teenage daughter Bill is arrested for ‘waving a scarf’ bearing the name of a proscribed organisation. The obvious implication is that the road from this direct reflection of events in modern day Britain and the vanishings and state violence depicted in Gliff is minimal. Elsewhere, the genocide in Palestine is a constant presence, both in straightforward discussions between the characters, and in the none-too-subtle subtext of the two historical war stories that thread their way through the book. Here, in the asymmetric warfare that is leading to the ‘flattening’ of an entire people, and in other dehumanising developments (such as the advance of AI which leads to key characters losing their livelihoods) Smith is setting the scene for the imminent dystopia she showed us in Gliff.

If here, as in that other book, there’s much that seems hopeless about the world to come, there are some seeds of hopefulness. As ever, Smith manages to add a lightness to the dark messaging via linguistic playfulness and the warmth of human (again, here, familial and specifically sororal) connections. In amongst these threads are the glimmers of hope: the resurrection of specific characters through the power of imagination, as a counteracting energy to the dehumanising forces at play (‘to imagine is to live’); the importance of paying attention, of not tuning out of the torrent of dismal news our devices expose us to on a daily basis; and the simple escape to be found in close connections (expressed in the sisters’ shared imaginings, fun with wordplay and intuitive understanding).

This is all very thought-provoking and relevant stuff, with a good amount of pleasure to be had in tracing the links between the two books (though that kind of exercise was far better executed by Smith in How to be both) and lots of sentence-level joy in the linguistic play that Smith clearly revels in. Ultimately, taken on its own and in its entirety, though, I found it a far less satisfying read than its sibling Gliff. While I found that book both an entrancing fantasy and a chilling reflection of extant reality, with a haunting quality that hung over me for weeks after reading (and I can still tap back into now), this one intrigued me more than it moved me.

Score

7.5

For me, for all its contemporary relevance and linguistic brilliance, taken on its own merits it feels to me like the lesser twin to Gliff. In some ways (to borrow a phrase from Smith herself) it feels more of a ‘companion piece’ than something that truly stands alone.

Like the sound of this one? Buy it at bookshop.org.

(If you click through and make a purchase, I may earn a small commission from Bookshop.org at no additional cost to you, which helps support local independent bookshops. I’ll only share these links for the highest rated titles on the site. )

Next up

Another book I’d have thought. Which book? We shall see.