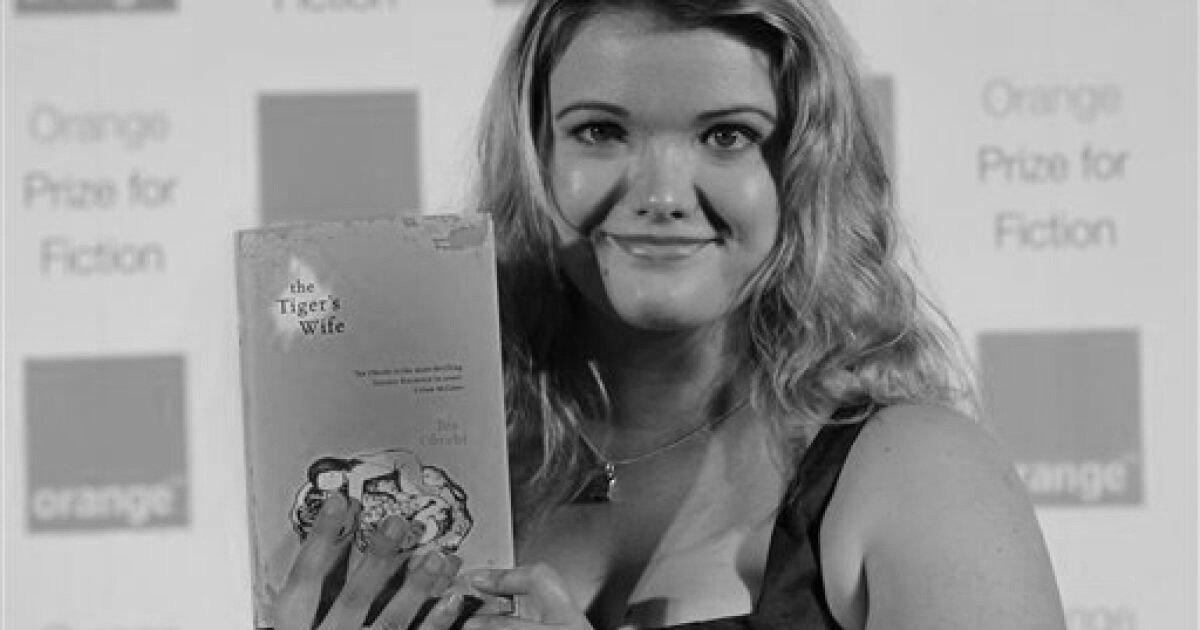

The Tiger’s Wife (2011)

Who wrote it?

Téa Obreht (born Tea Bajraktarević; 1985- ; active 2009- ) born in Belgrade, Serbia (then Yugoslavia). She was brought up by her mother, and was very close to her maternal grandparents, a Catholic Slovene of German origin and a Muslim Bosniak. When the Yugoslav Wars began in the early 1990s, they moved, initially temporarily, out of caution. They moved first to Cyprus and then Cairo. Her grandparents moved back to Belgrade in 1997 but she and her mother settled in the USA, first in Atlanta and later California.

She studied at the University of Southern California, before moving to Cornell where she received an MFA in fiction from their creative writing faculty. She wrote short stories, which were published in the New Yorker and the Atlantic, as well as her debut novel (initially a short story itself), The Tiger’s Wife, which was published in 2010. As well as taking home the 2011 Women’s Prize, it was shortlisted for the US National Book Award for Fiction. Her second novel, Inland, was published in 2019. Both of her novels have also been shortlisted for the Dylan Thomas Prize for young authors.

What's it about?

The Tiger’s Wife is set in a semi-fictionalised version of the Balkans, on the border between two unnamed countries, and takes place through a sweep of the twentieth century, in a period notably covering the Second World War and the Balkan conflicts of the 1990s. Its central character is Natalia, a young doctor who is on a mission of mercy to an orphanage. In the present day, she finds herself facing the double mysteries of her suspicious hosts, who spend their time digging for something in the surrounding land, and of the recent death of her grandfather, who took himself to a remote village to die.

It’s particularly in her exploration of her grandfather’s death that the story begins to jump back to tales of his youth, some of which he told Natalia and some of which she uncovers. Central are the tales of the titular Tiger’s Wife, a deaf mute woman who develops an unusual relationship with a loose tiger who terrorizes a village during the Second World War, and the ‘deathless man’, a character who seemingly cannot die and haunts her grandfather through a long period of his life. Along the way, we also meet a range of memorable characters, as Natalia tries to make sense of both the past and present.

What I liked

Oh wow, this is a really tough one to break down! I’ll begin by saying that the atmosphere it creates is genuinely brilliant. There’s a real sense of strangeness about it, in the blurring of myth/superstition and reality.

Its highlights are undoubtedly in the retrospective passages, particularly those around the tiger. There’s a section told from the escaped tiger’s perspective that is absolutely entrancing. And there are equally evocative, vividly realised moments such as when Natalia’s grandfather takes her to see an escaped elephant walking through the city at night, and all of the encounters with the deathless man, most particularly the initial drowning scene.

Within it there are also memorable characters, the best of which feel like symbolic figures drawn from the pages of mythology.

The fact that much of the novel’s descriptive period takes place during wars taking place literally on the doorsteps of its characters, yet it chooses to focus much of its energy on strange stories that have only tangential (if any) relevance to those wars, is super interesting and obviously deliberate. From what I could gather, the gist of the message is around the power of storytelling / collective mythology to unite and provide solace / sense-making in the face of conflict and divisions (some of which - particularly those of the Balkan civil conflict - feel very difficult to explain on their own terms, notably to some of the characters experiencing them1)

There’s a relentless sense of adventurousness about it. It doesn’t always work, but when it does it’s stunning and all the more impressive as the debut novel of such a young writer.

What I didn’t like

As the above all probably points to, it’s not the most straightforward read. It’s evidently deeply allusive and metaphorical. This can bring great rewards, when something clicks and makes sense, but it can also provide periods of frustration if you’re not quite in the mood for a cryptic mystery. I found I enjoyed it most when I stopped worrying about all of that and just enjoyed its language, atmosphere and mood.

By the end, I did find myself struggling to disentangle myth from reality from myth-infused reality, etc. Hence it taking me a while to gather the strength to try to summarise it.

I was generally less inspired by Natalia’s present-day narrative. In some senses it’s merely a framing device for the incredible stories of her grandfather’s life, but there is more time spent on that framing than I felt was necessary and it dragged at times. The ending was also a bit underwhelming as a result.

Food & drink pairings

Rakija

One’s own legs

Fun facts

At 25, Obreht was the youngest winner of the Women’s Prize to date. The previous year, she’d also been the youngest name on the New Yorker’s list of best writers under 40.

Emma Donoghue’s Room was the bookies’ favourite to win, a bestseller already and Booker nominee from the previous year. It did win the vote of the Prize’s ‘Youth Panel’ in which a panel of teenagers chose their favourite, though, so that’s something.

Vanquished Foes

Emma Donoghue (Room)

Aminatta Forna (The Memory of Love)

Emma Henderson (Grace Williams Says It Loud)

Nicole Krauss (Great House)

Kathleen Winter (Annabel)

Room was also on the 2010 Booker shortlist, losing to Jacobson’s much-loved (I jest) The Finkler Question.

2011’s Booker Prize went to Julian Barnes for the slim and understated The Sense of an Ending.

Context

In 2011:

Anti-government protests began in Tunisia in late 2010 spread across the middle east in the so-called Arab Spring, dominating news for much of the year

Osama bin Laden killed in a US military operation in Pakistan

Huge earthquake and subsequent tsunami in Japan kills more than 15,000 and sparks the Fukushima nuclear disaster

Riots erupt in London and other UK cities following the murder by police of unarmed black man Mark Duggan

Occupy Wall Street protests begin in the US

Far-right terrorist Anders Breivik kills 77 in a bomb blast and youth camp massacre in Norway

Basque separatist group ETA declares end to 43-year campaign of political violence

Ongoing European sovereign debt crisis, including bailout of Portugal and writedown of Greek bonds

North Korean leader Kim Jong-il dies

Guantanemo Bay document leaks by WikiLeaks

Wedding of Prince William and Catherine Middleton in the UK

South Sudan cedes from Sudan, following an independence referendum

Yuval Noah Harari, Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind

Daniel Kahneman, Thinking, Fast and Slow

Haruki Murakami, 1Q84

Ernest Cline, Ready Player One

Adele, 21

PJ Harvey, Let England Shake

Jay-Z & Kanye West, Watch the Throne

St Vincent, Strange Mercy

Drake, Take Care

Kate Bush, 50 Words for Snow

The Artist

The Help

Moneyball

Harry Potter & the Deathly Hallows - part 2 (final movie)

Life Lessons

Stories are important. Whether or not they make any sense.

Score

8

Some genuine magic in here, but counterbalanced by a bit too much going on, some of which I didn’t have the energy to get my head around properly.

Ranking to date:

Property (2003) - Valerie Martin - 9.5

The Idea of Perfection (2001) - Kate Grenville - 9

Half of a Yellow Sun (2007) - Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie - 9

The Lacuna (2010) - Barbara Kingsolver - 9

When I Lived in Modern Times (2000) - Linda Grant - 9

Larry’s Party (1998) - Carol Shields - 8.5

Bel Canto (2002) - Ann Patchett - 8.5

Small Island (2004) - Andrea Levy - 8.5

A Crime in the Neighbourhood (1999) - Suzanne Berne - 8.5

The Tiger’s Wife (2011) - Téa Obreht - 8

On Beauty (2006) - Zadie Smith - 8

A Spell of Winter (1996) - Helen Dunmore - 8

The Road Home (2008) - Rose Tremain - 7.5

We Need to Talk About Kevin (2005) - Lionel Shriver - 7.5

Home (2009) - Marilynne Robinson - 7

Fugitive Pieces (1997) - Anne Michaels - 6.5

Next up

Next up on the Women’s Prize reading list is 2012’s winner The Song of Achilles, by Madeline Miller. I may skip off on a diversion first, though…