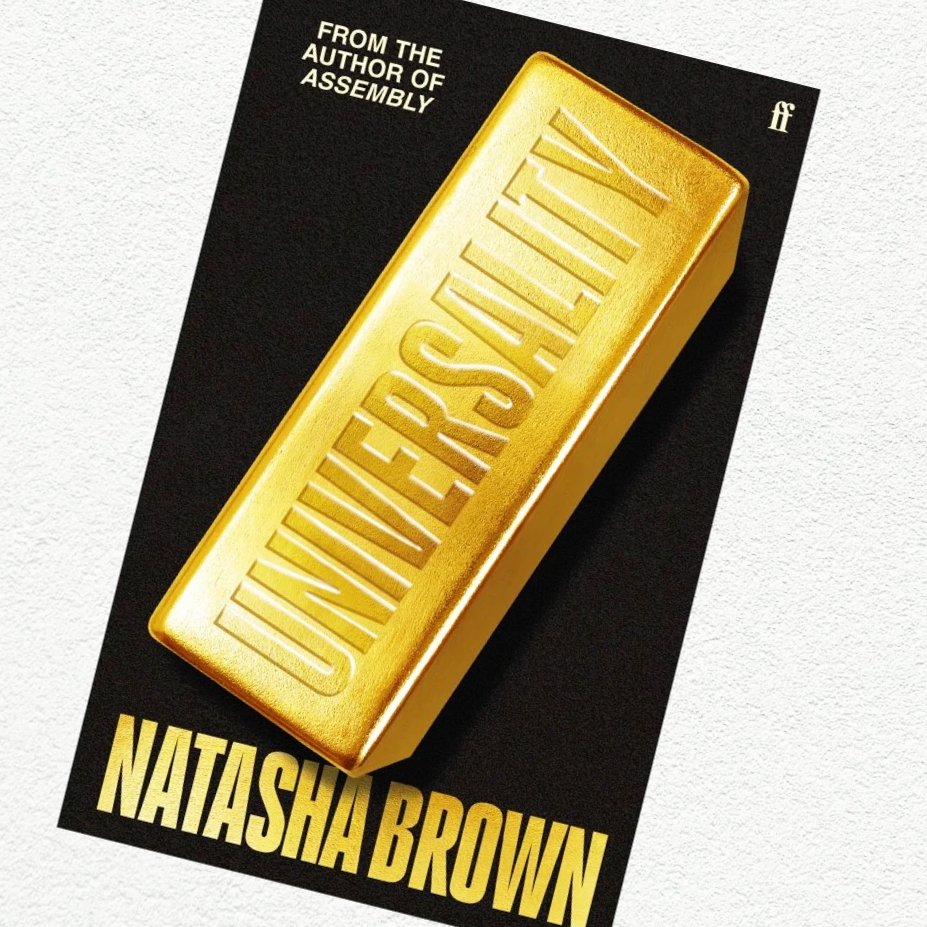

Universality (2025)

Why this one?

More Booker longlist reading. Why did I pick this one? Very good question, to be honest. More on that later…

Natasha Brown (1990- ; active 2019- ) was born in London, and is of Jamaican heritage. She studied Mathematics at the University of Cambridge and spent more than a decade working in the financial services industry. She began writing in her spare time before receiving a London Writers Award in 2019 which enabled her to develop her first work.

Her debut novel, Assembly, was published in 2021 to huge critical acclaim. It was nominated for the Goldsmiths Prize, the Folio Prize and the Orwell Prize and won a Betty Trask award in 2022. It has been translated into 17 languages. Brown was included on Granta’s prestigious once-a-decade Best of Young British Novelists list in 2023, and was recently announced as Chair of the judges for the International Booker Prize 2026. Universality is her second novel and like her debut was also shortlisted for the Orwell Prize.

Thoughts, etc.

Universality begins with a long first section written in the style of a journalistic ‘long read’. It recounts the tale of a crime which took place at an illegal rave on a Yorkshire farm, in which the leader of a radical anarchist movement is bludgeoned with a gold bar by a young man called Jake. In the article, presented as a kind of moral parable about class and wealth based divisions in our society, we are introduced to Jake’s mother, a populist ‘anti-Woke’ columnist who goes by the name of Lenny. We additionally meet Richard Spencer, the owner of the farm whose gold bar was used in the crime. He’s a wealthy banker who is presented as symptomatic of the ills of capitalism.

Once this tale has been told (we learn, by a young freelance journalist called Hannah) the novel takes us into the voices of various other narrators, including those we’ve met in the article. Through the remainder of the book (spoilers ahead for those who haven’t read it!) we learn new information about all of the characters in the article that lead us to reassess our initial perspective. Hannah is a struggling journalist who has made significant compromises in the writing of the piece to make it more ‘marketable’ in an ultra competitive landscape.

Crucially, the novel reveals that far from the purely political and contemporarily ‘symbolic’ crime that Hannah sets up in the article, there are far more personal motivations at play behind the scenes. Most notably, we discover that Lenny is in a relationship with Spencer. Spencer himself is revealed as somewhat more human (only somewhat, though) than the cliched banker we are introduced to (hey, his gold bar wasn’t even solid gold!) and Jake’s crime takes on a somewhat more personal dimension when we learn of his shunning by his awful mother and her relationship with the man whose ‘weapon’ he used.

Lenny herself commands much of the attention in the rest of the book, which seems to be building to a grand climax at which she speaks at a literary festival. Her ‘anti-Woke’ ideology is relatively swiftly revealed to be largely careerist pragmatism. She’s essentially a moral vacuum who is happy to adopt and modify her politics to whatever will keep her employed, popular, and rich. This apparently also extends to her choice of partners. To the public, of course, she keeps her family connections (and indeed her own personal roots) well hidden - the only things that matters is that they know she is ‘not Woke’ and ‘not London’.

It’s a book that his received fulsome praise from many quarters, with many a five star review and plaudits from respected sources and prizes aplenty. I have to confess that my immediate reaction to all of this was utter bemusement. At a very basic level, I did not enjoy the experience of reading this book at all. The first third (in which the seemingly exciting story promised in the blurb unfolds) is lumberingly written, and didn’t grab my attention at all. Of course, this is soon revealed to have been something like “the point” - we are deliberately given a piece that is in the style of clickbaity (all be it relatively high-end clickbaity) journalism, and it’s sort of necessary that that is done authentically for the novel’s structure to work. The trouble here was that I find these kind of generic articles pretty tiresome to read, and that was the case here too - so regardless of whether or not it’s structurally important, it didn’t excite me and I would have put it down at this point were it not a Booker longlistee.

Arriving at the book’s big stylistic shift already exasperated (and already having moaned to my partner about it reading like ‘bad journalism’) I wasn’t in a great frame of mind to enjoy the rest of the book. My primary criticism is that the rest of the book, even as its structural ‘cleverness’ becomes apparent, lacks redeeming features over and above this cleverness. Some positive reviews have used its ‘puzzle-like’ structure as a compliment - to me, it was a frustration. The puzzle is not a compelling one to solve (I didn’t care about any of the people in the article or their circumstances) and nor is the solution an especially satisfying one.

Beyond that, what else is there? The characters are caricatures in service of the cleverness. It’s implied that the later sections of the book reveal hidden depths beyond the superficiality of the article, but do they really? I found none of them especially compelling. Lenny is simply the embodiment of everything wrong with the modern world, and so obviously so that she’s effectively a straw figure that doesn’t merit the constant eyebrow-raising and nudge-nudge wink-winking in her direction. Oh, she’s ‘anti-Woke’ but now writes for The Observer?! Consider me utterly shocked. Spencer? “Bankers also cry” - I didn’t care! Hannah is somewhat more interesting, I think. A different book that spent more time with Hannah, her awful friends and her conflicted attempts to balance earning a living with selling her soul could have been far more interesting. The hints of the movie version of her article in which the producers have re-cast Jake as a young Black man and Hannah’s attempts to justify this as rational and ‘truer’ than her ‘true story’ were among the book’s few laughs (along with Spencer’s hollow gold bar, even if that one was a bit on the nose).

I get the point (and did while reading) that Brown is deconstructing the simplistic narratives we are fed in the modern, highly polarised ‘Culture Wars’ landscape, and massively agree that this is a worthwhile endeavour. But isn’t it preaching to the converted? Don’t most readers of this kind of literary fiction understand inherently the false dichotomies being established and understand that the characters espousing them are often deeply compromised individuals with ties to the things they criticise and that their motivations aren’t exactly honourable? No?

This is a book that is dealing with important issues which I am glad to see raised, and maybe its appearance will lead to some people seeing something new in our hateful world of ‘woke’ and ‘anti-woke’ (urgh) as a result. But there are ways of making these points in more subtle ways, in books which also remember to include concepts such as a compelling plot, believably human characters and some sort of emotional heart.

Score

3

That’s 3/10, for any new readers. I’m not normally this damning, I have to say, but this one just did not connect with me on any level. The points are in acknowledgement of the unusual structure, more than anything else, but for me this was more semi-satisfactory thought experiment than engaging fiction.

Next up

One Boat.