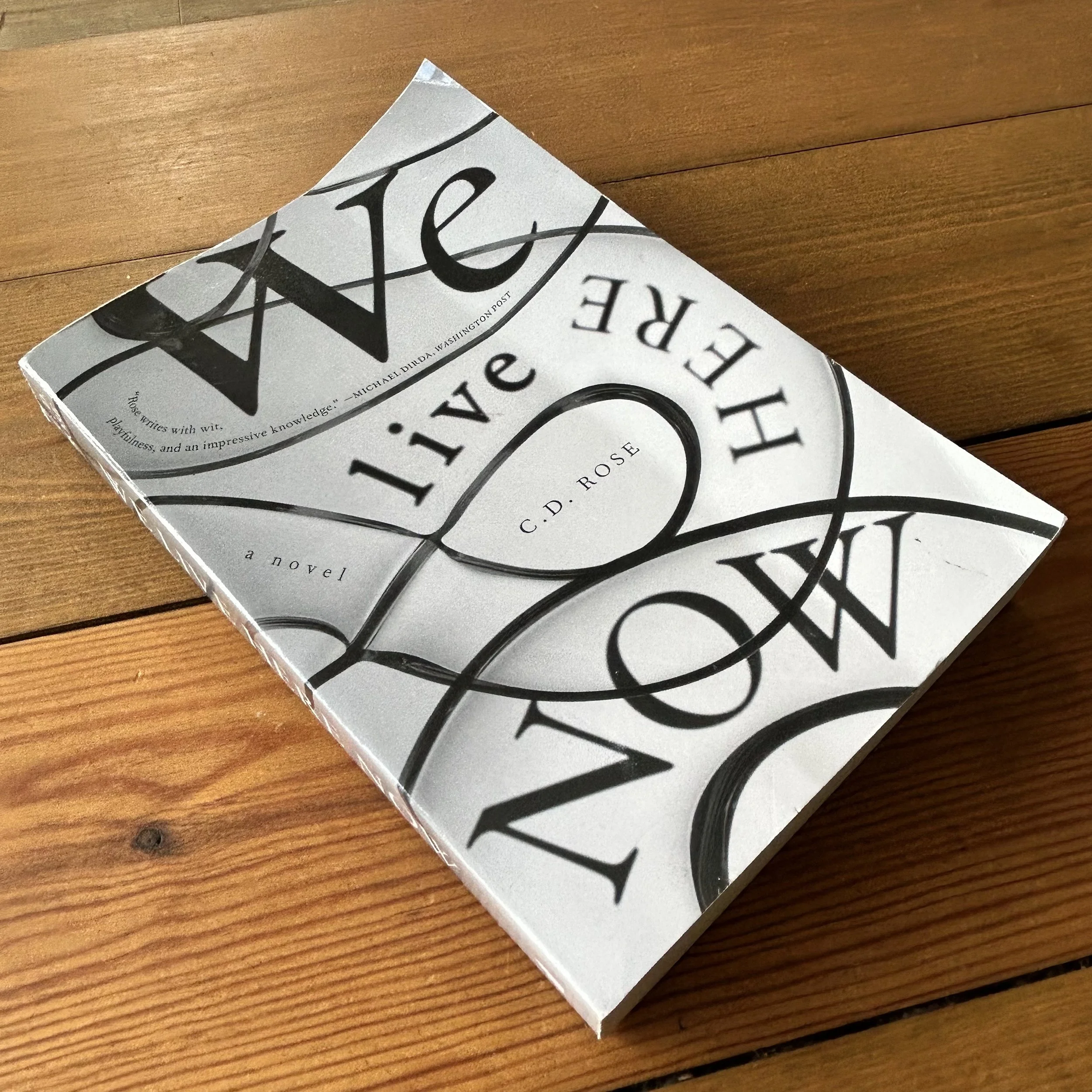

We Live Here Now (2025)

Why this one?

It won the Goldsmiths Prize last year, which I don’t follow quite as religiously as some of the other major prizes, but sometimes think I should. This year’s shortlist also included a couple of my favourite recent debuts in We Pretty Pieces of Flesh and Nova Scotia House and past winners have included excellent books that I’ve covered on the blog by Benjamin Myers., Ali Smith and Eimear McBride, among many others that I really should also get around to reading.

C. D. Rose (“late 1960s”-; active c.2013-) was born in Manchester, England. He holds an MA in Creative Writing from the University of East Anglia and a PhD in Creative and Critical Writing from Edge Hill University. He has worked internationally as a teacher and trainer, including a decade-long tenure with the British Council in Italy and shorter periods in Lebanon, Morocco, Russia, and the United States. He currently lives in Hebden Bridge, West Yorkshire, and teaches creative writing and literature at the University of Birmingham.

Rose’s previous novels form a "parafictional" trilogy (exploring themes of lost books and forgotten authors): The Biographical Dictionary of Literary Failure (2014), Who's Who When Everyone Is Someone Else (2018), and The Blind Accordionist (2021). His short story collection Walter Benjamin Stares at the Sea (2024) was shortlisted for the Edge Hill Prize. He is a Fellow of the Royal Literary Fund, and has edited the anthologies Cities: Birmingham (2018) and Love Bites: Fiction Inspired by Pete Shelley and Buzzcocks (2019)..

Thoughts, etc.

We Live Here Now is a set of fourteen short stories set in various corners of the modern world, connected (thematically and often more directly) by their positioning within the broad landscape of modern art and its intersection with commerce and capitalism. It begins with a fictional article by the critic Che Horst-Prosier about the equally fictional artist Sigi Conrad, who has disappeared following her most recent exhibition, which has become notorious for the apparent ‘disappearance’ of a number of its attendees. We are then introduced to twelve characters, seemingly all in some way connected to or impacted by Conrad, across the book’s stories, before most of the cast are reunited (for unclear reasons) in attendance at a mysterious talk, before we return to another article by Horst-Prosier on Conrad’s return, for an exhibition purportedly taking the form of a ‘Klein bottle’ (a device in which inside and outside are the same) and things get even weirder.

I do say this sort of thing a lot, but it really is very difficult to know where to start with this one! I raced through it, really loving some of the stories and enjoying most, and then ended it feeling surprisingly underwhelmed, and perhaps with a bit of a sense that I wasn’t quite smart enough to have ‘joined the dots’ in what is ultimately a highly confounding book. For the most part, though, it’s easy to be carried along by its many qualities. The writing is punchy, concise and never needlessly difficult (on a sentence level) even when covering very complex subject matter. There’s a huge amount of humour in here too - some of it rather dark and obtuse, but some just straightforwardly funny (like the invented naming convention for the succession of slick black SUVs that crop up throughout the book - Lexus Punishers and suchlike). Many of its characters feel rounded and human, and hugely memorable, despite their relatively brief amount of page time. And perhaps most impressive is the overall mood throughout, in which reality is constantly subtly ‘off’, not quite right, a general uneasiness that occasionally tips over into memorably rendered reality-obliterating weirdness or nightmarish horror. It’s all hugely cinematic and immersive.

Some of the sections I liked most were those that felt most clearly purposeful in their connection to the central figure of Conrad and her work. Early in the book we meet Kasha, a dealer who sells a work by Conrad which then goes off on a global journey via sea containers for insurance / tax dodge purposes. When its mystery buyers appear to demand a viewing, they are greeted with an empty container. Kasha tries to spin this as ‘the point’, and for all we know it might be. Elsewhere we find those containers described as works of art in themselves, in another great section called ‘Manifest’ in which we go deep into the world of sea containers on a global voyage in which this time Conrad herself appears to be an unusual passenger. In this section, we learn a lot about sea container disasters, especially fires. I also liked the story in which one of Kasha’s acquaintances (boyfriend?) Silas becomes caught up in art collecting, and ends up with his own Conrad, which contains more than he bargained for. And that of Ryan, a Richter-esque artist whose usual mode is to create paintings that erase their subject matter, who becomes the unlikely choice to create a new portrait of the CEO of Laerp, an industrial conglomerate focused on undersea cables (and, yes, also apparently something to do with shipping containers). The section on Rachel Noyes (no/yes indeed), a sound artist who is sent to Berlin to apply for a job she knows nothing about, is seemingly unable to leave her slick apartment and in any case realises the interview is actually via video call, is brilliantly Kafka-esque and maybe a contender for my favourite in the book.

There are some other sections which feel less fully formed and more tangential to the main through line of the book. ‘Ich verstehe nur Bahnhof’, despite its excellent title, kind of drifted over me in its depiction of a man who constantly rides around on underground trains. There’s another story about another guy who makes sound recordings. Elsewhere there are several stories that have engaging Black Mirror style concepts, but don’t really seem to go anywhere (a man keeps having near-death experiences; a scientist has his identity stolen by multiple people; a woman has a job in an upmarket private members’ club in which there’s a secret room she’s not allowed to enter; etc.) All of these are actually still incredible pieces of writing, excelling in that ability to build a mood of unease and dislocation. Like the rest of the book, they recall works by some of my favourite authors (Auster, DeLillo, David Mitchell; others have repeatedly referenced Borges and Calvino). But I was never quite sure what to make of them, either in isolation or as a whole.

I think it’s that last point that slightly dented my enjoyment of a book that I really loved the experience of reading. As I’ve said a few times on this blog, I’m not the sort of reader who gets annoyed at an open or inconclusive ending. In fact I’m quite fond of being left with a bit of work for the imagination, or fuel for discussion. The difference in this one I think is that it doesn’t seem to be pointing towards a ‘make of this what you will’ type conclusion, but rather suggesting that there is a kind of code to be unlocked, and if you haven’t cracked that code, you’ve missed the point. That sort of (vaguely modernist I guess?) approach I find harder to deal with, probably because it makes me feel a bit stupid. I could be wrong here, it may be that the seemingly intricate web of connections and references that litter the book are just there in the spirit of playfulness, rather than to be pieced together to form a solution to a cryptic crossword clue.

Perhaps it’s better to turn to Rose’s own well-chosen words, in a New Statesman interview talking about the Goldsmiths Prize and ‘innovation’ in writing:

”“Innovative” approaches ask more of the reader, and often offer no easy rewards. You may be asked to read more carefully, more slowly, or to re-read. Your time will be needed. You might not find closure, or resolution, or revelation. A book with an innovative approach will not be a love letter to anything. It will not tell you about “what it means to be human.” It will deliver no message. It cannot be easily summarised. It will demand your close attention, and might leave you bereft and adrift. But, Lord, you will have experienced something.”

However much you enjoy the various facets of ‘innovative’ works he’s describing here (I like some aspects and find others a source of frustration) it’s impossible, when considering We Live Here Now, to argue with that last sentence. You certainly will have experienced something. Quite what, is less clear, and I certainly did leave that experience feeling somewhat ‘bereft’ and very much ‘adrift’. But it was, as they say, a hell of a ride.

Score

9

Ultimately I think this does exactly what a Goldsmiths winner should: it leaves you with more questions than answers, upends your notion of what a book should or shouldn’t be, and kind of messes with your head a bit. With all that, there will be inevitable frustrations, but I think on balance they’re more than worth tolerating given the quality of that overall ‘experience’.

Like the sound of this one? Buy it at bookshop.org.

(If you click through and make a purchase, I may earn a small commission from Bookshop.org at no additional cost to you, which helps support local independent bookshops. I’ll only share these links for the highest rated titles on the site. )

Next up

I have a few lighter non-fiction reads/ audiobooks on the go, which probably won’t make it to the blog, but other than that I might get back into a few upcoming Netgalley releases.